AS 201 The Warring States Period in China

CHAOS = PROGRESS

(see http://www.china-mike.com/chinese-history-timeline/part-2-warring-states-period/)

As our textbook points out, during the Eastern Zhou period, warfare was still somewhat ritualized; it was a gentleman's affair, conducted by elite mounted soldiers. Sometimes, the time and place for the battle was agreed upon in advance. Honor was probably more important than grand strategy.

All this changed in 400-300 BCE. Armies were no longer composed of elites, gentleman "knights" leading armies numbering in the 1,000s; maybe 10,000 would have been a huge army in those days. Now we are talking about peasant conscript armies numbering several hundreds of thousands. Warfare became totally destructive; it was conquer or be conquered. Troops were trained and equipped with more deadly weapons like crossbows with their bronze trigger mechanisms that could be shot from a charging horse. Battles were about sieges and destroying walled cities, murdering or enslaving the inhabitants, as circumstances dictated. It was a brutal and disturbing time. But it was also a time of such fierce competition that lots of innovations were spurred.

One benefit of all this turbulence: Chinese civilization moved forward.

Money (bronze coins) is widely circulated.

Iron tools revolutionize agriculture as well as warfare– including developments such as the crossbow, riding on horseback, and cavalry warfare.

Iron tools revolutionize agriculture as well as warfare– including developments such as the crossbow, riding on horseback, and cavalry warfare.

Chinese calligraphy becomes more fluid and expressive with the introduction of brush writing.

The first canals are built along with long defensive walls separating rival states (some of which would later become the Great Wall).

THE HUNDRED SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT

But the most significant development was a flourishing in social philosophy and political theory known as The Hundred Schools of Thought--not literally a hundred different idea sets, but a plethora of them, and they kept multiplying. There was fierce comeptition to come up with ideas about how to organize these small states and maximize their productivity. During this turbulent period, rulers wanted to know the best way to conquer and govern. There were educated men who traveled around from kingdom to kingdom explaining their philosophy of how to govern and manage a large population and keep them peaceful and productive. It was all about Statecraft.

Brief Video

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War came from this period (His key message to “Attack your enemy’s strategy first, his troops second” would not be lost on Mao Zedong 24 centuries later).

An Axial Age: Do You Know What The Term Means?

The Axial Age (also called Axis Age) is the period when, roughly at the same time around most of the inhabited world, the great intellectual, philosophical, and religious systems that came to shape subsequent human society and culture emerged—with the ancient Greek philosophers, Indian metaphysicians and logicians (who articulated the great traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism), Persian Zoroastrianism, the Hebrew Prophets, the “Hundred Schools” (most notably Confucianism and Daoism) of ancient China….These are only some of the representative Axial traditions that emerged and took root during that time. The phrase originated with the German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers, who noted that during this period there was a shift—or a turn, as if on an axis—away from more predominantly localized concerns and toward transcendence.

It was a pivotal time in early human history because human beings began to reflect for the first time about individual existence, and the meaning of life and death. In answer to this, people began searching for more comprehensive religious and ethical concepts, and to formulate a more enlightened morality where each person was responsible for his own destiny. So, between approximately 900 and 200 BCE, a new mode of thinking developed almost simultaneously in four distinct areas of the world. See http://www.humanjourney.us/axialintro.html

So, in Judaism, it was the time of

--Isaiah, 770-700 BCE, followed by the “Age of the Prophets,” 650-600 BCE.

--In Iran, we saw the great Zoroaster, ca. 600 BCE.

--In India, of course, there was the great teacher Shakyamuni, the Buddha, 563-483 BCE, and the Upanishads and Vedas appear ca. 550 BCE.

--In Greece, there were the three great philosophers:

Socrates, 469-399 BCE,

Plato, 427-347 BCE, and

Aristotle, 384-322 BCE,

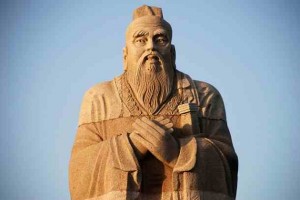

--while in China we had Confucius, 551-479 BCE; and Laozi, 606-530 BCE??, Mozi (480-390 BCE), Mengzi, Xunzi, Zhuangzi, etc.

Differences between Chinese and Western Philosophy

It is often said that the aims of Chinese and Greek philosophy were different.

The Greeks aimed to understand the human experience in terms of three basic questions: 1) What is the world made of? or What is there?; 2) What should we do?; and 3) How can we know? What is knowledge and what does it mean to have some?

In other words, these are ontological questions about being, existence, and the meaning of life. Why are we here? What is the world? How should we live?

Chinese philosophy, by contrast, was born during this intense period of political and social breakdown so the questions were driven by more urgent questions of

--How do we survive in this uncertain time?

--How should we behave or conduct ourselves in these fluid, changing circumstances?

Therefore, given the circumstances of its birth, Chinese philosophy perhaps did not have the luxury to be as speculative as Greek philosophy was. It had to come up with answers.

--Knowledge for what purpose? Not for abstract or for provide answers to ultimate questions, but something useful for immediate survival purposes.

--Confucianism, Moism, Legalism and Daoism all came up with their responses. They were quite different in their approaches, of course, and some lasted, endured and became central, while others did not.

--When Confucius died in 479BC, he was only mourned by a small group of his disciples; his fame and high reputation came much later when his thought was installed as the official teachings of the Empire in the Han dynasty, long after his death.

There will be much more to say on Confucianism later, but, in a word, Confucius felt that with things falling apart around him, the best thing for intelligent people to do was to preserve what was great about the old system, that of the early Zhou rulers, who established a universal kingship under a ruler who was known as the "Son of Heaven" (tian, 天); that is, he claimed authority to rule from the Will of Tian, aka "The Mandate of Tian or Heaven."

Confucius himself--aka Kongzi (551-479 B.C.E.)--did not leave behind any books by his own hand, though he may have authored the Spring and Autumn Annals an historical account of his native state of Lu; and he no doubt compiled and edited the collections with which he worked. He is believed to have written influential Commentaries on the Yijing, a book he valued very highly. Because he was defintely a teacher, he had to create a curriculum for his students, and he had to have some materials to go over with them. He drew upon materials that were already around, that could be found in the Six Books: The Books of History, Poetry, Music, the great Book of Changes for Divination, and the Book of Rites (Li) or proper Rituals for departed ancestors, and the aforementioned Spring and Autumn Annals which offered insights into understanding the art of Statecraft and Diplomacy.

The goal was order in the family and in society; eventually the state, the kingdom and the entire "Realm" or "All Under Heaven" (天下). So, in ancient China, it was about knowledge for a specific purpose: how to bring order and stability to the country and how to manage the realm, the state or the kingdom. Confucius accepted the reasoning of the early Zhou monarchs who saw the Cosmos as offering a model for a haromonious order that humans could and should emulate. If we look up to the Heavens--and most early Chinse scholars were astronomers of a sort--we observe the planets moving in a prescribed and regular order. Why shouldn't human society function analogously? To do this, people had to perceive and know the order--to grasp the political and social hierarchies--starting with the family and building up to the state. And what better place to learn and internalize these principles than in the conduct of Li or Ritual.

Confucius expected learned men to practice "the Way" so that they could manifest ren (仁), often rendered as "Goodness," "Benevolence," or "Human-heartedness,” but also can be thought of as “authoritative conduct” (Ames and Rosemont). The character 仁 depicts "person" and the number two; so, people numbering two or more, i.e., human beings in community, in relationship to one another. You have to know how to treat and respect others in order to get along properly. To do that, you needed knowledge (知), i.e., the capacity to know correct action and follow it. Also, a person should be upright, moral, trustworthy and courageous.

All of these could be furthered by correct practice of Ritual (Li 禮), or “observing ritual propriety,” he believed. And people who had these characteristics, could manifest a certain charismatic power he referred to as “Excellence,” “Efficacy,” or often, Virtue (徳). The people capable of manifesting this power, this Excellence or Virtue, were the best prepared to assume leadership and authority in the community. He called them “Exemplary Persons” though the literal term is "Princelings" or Junzi 君子 which means an offspring of the Aristocracy or Nobility, people with authority; but while the term "junzi" originally signified scions of the aristocratic or noble class, in Confucius' system, he tied this title--which is often rendered into English as a Noble Person, a "Gentleman," or a "Superior Person"—to Education and training: that is, he established the grounds for the credentialing that people needed to claim the right to be “Exemplary Persons,” eminently qualified to lead and rule. This was a new and innovative idea: the right to rule and govern was linked with the quality of Excellence or Virtue (徳) which included a notion of Charisma and Energy, of Efficacy or Effectiveness.

To do that, you needed knowledge (知), i.e., the capacity to know correct action and follow it. Also, a person should be upright, moral, trustworthy and courageous. All of these could be furthered by correct practice of ritual (Li 禮), he believed. While we tend to think of Ritual as static, rigid even stultified, it can be very dynamic, especially when we combine ren (仁) and (Li 禮). That is, mastery over all the social forms and fomalities that life or society requires of us, frees up the self to do what is natural and right in the world, or what is appropriate and correct. And that would be what is ren (仁)--something good and beneficial to others. But people cannot manifest, cannot exude this "authoritative" air without all the training and discipline that Ritual (Li 禮) requires of us. Once mastery over the forms is achieved, however, one can manifest ren (仁) and do so effortlessly.

So, people who can do this, who possess these characteristics, could manifest a certain charismatic power often called De or Virtue (徳) but it might equally well be called "efficacy" or "excellence." The people capable of manifesting this power, this Virtue or Excellence, were the best people prepared to assume leadership and authority in the community. Confucius used the common term "Princelings" or Junzi 君子 which literally means the offspring of those with authority; but while the term "junzi" originally signified scions of the aristorcratic or noble class, he was radically redefining what the term meant and how one becamse a Junzi 君子. In Confucius' educational paradigm, he tied this title--which is often rendered into English as "Gentleman,""Superior Person" or "Exemplary Person"--to Education and training: that is, he established the grounds for the credentialing that people needed to claim the right to lead and rule.

This was a new and innovative idea: the right to rule and govern was linked with the quality of Virtue or Excellence (徳) which included a notion of Charisma and Energy, of Efficacy or Effectiveness. This, in turn, was tied to Education and Learning. Being educated meant being literate in the classics. It meant knowing about History, Diplomacy, Poetry, Music, and understanding the underlying Cosmic Principles in the universe and how they relate to the flow of events (see the amazing Book of Changes), plus an understanding of correct or appropriate Ritual conduct, and allowing all of these to combine and yield insight into human behavior--these are the qualities that a true leader needs; and true leaders were what the times called for. Moreover, these qualities were beginning to be no longer tied exclusively to lineage, to nobility, to one's birth into the aristocracy. Now you could be trained or educated into these qualities with the correct curiculum and the appropriate practice of the principles learned in these new educational insitutions, these private academies like the one Confucius pioneered.

Daoists were worried about people becoming too caught up in a superficial, outward-looking set of rules and practices to the detriment of looking inward, to the inner self, or to what they called the Great Way of Nature and the Cosmos, a "Way" that transcends human life and takes all of nature and the universe into account. The problem with all this book learning and Ritual Practice that Confucius espoused was inherent in the basic problem of Language and how it structures and limits perception, and therefore, our understanding. Language consists of "naming" things but as soon as you name them, you are trying to fix these names and make something that is inherently fluid, static. It won't work. So, Daoists don't have a problem with practicing and maniferting Ren 仁, for example; it fact, they want more of this. But is 知 or Knowledge the best or only way to get there? Or is knowledge just a way that the Mind is trained to "discriminate" among countless things in the world, to create false and misleading binary categories (good, bad, bright, dull, long, short, etc.) just clutter up a mind that basically wants to be free and to become One with the Cosmos.

For Confucius, the Way was the Way of the Ancients, of the Sages; it was modeled on various practices of he Early Zhou Dynasty. For Daoists, too, the Dao (道 ) or the Way was also the Way of the Sages but it was the ancient wisdom that goes way back in time, before society became so complex, disordered and violent. It goes back to those who valued Oneness with nature, and with the Universe, to those who appreciated living in harmony with nature and with each other. So it emphasizes a non-attachment to all the desires for power, for dominating others, for greed, for material gain, wealth, status, rank, etc. In its terse language, it tries to expose these things for what they are: all big fat illusions. Daoists say that in the end, none of these things really matter; if you live your life free of these pressures, you will wind up being happier and probably be recognized as a great and wise person--a Sage--anyway. Just don't feel you have to TRY and Strive so hard. It is not so much that there is something wrong with Confucian knowledge; just don't be fooled into thinking that is all there is. That kind of knowedge creates the "Discriminating Mind"; why not be more like the newborn baby and see everything with eyes wide open, but eyes that do not focus on any particular object; instead, they just take it all in. It is the grand "gestalt."

Legalism was at the other end of the spectrum but in the short term, it was best suited for the times. The ultra-totalitarian Legalists had a dimmer view of man—believing that order needed to be imposed with an iron fist (Mao Zedong would later become a big admirer). Make the laws clear and the punishments swift and harsh for notcomplying with these laws.

“In a well-ordered nation,” the Legalist evil genius Shang Yang wrote, “punishment is endemic, reward scarce.”

The state of QIN—adopting the Legalists’ harsh system—would eventually conquer all other rivals to become the last state standing. They did the dirty work of unifying a huge geograhic area and this required hammering a variety of cultures into line and regulating everybody. It was so harsh, though, that the Qin system did not survive its first ruler, the great unifier, Chin-shih Huangdi. Instead, the Confucian approach came to be seen as the more reasonable, "middle way"; it was more civiilzed, grounded, as it was in high ethical principles, and it came to be seen as a much more humane way to rule. So the first Empeor comes to be seen as the model for HOW NOT to govern. Confucianism offered the best ideas for how to rule and stood up to the test of time for the next two thousand years.

Instructions